Finding the Good

As tornadoes ripped through our community this September, we witnessed firsthand the devastating power of these storms and the loss they can cause. But we also witnessed the power of natural disasters to bring communities together for the common good in ways both big and small. Neighbors braved the weather to warn us of a downed power line in our yard, groups came together the day after the storm to clean up the grounds of Sibley Elementary, church groups brought chainsaws and lasagna to people in need, and community members came together to help repair local farms and businesses. I’ve never had so many people ask how we were doing in such a short time.

As it turns out, tornadoes have a history of bringing out good in the people of Southeast Minnesota, and one of our state’s most recognizable institutions, the Mayo Clinic, owes its foundation to a tornado that devastated Rochester in the summer of 1883. The tornado took only about five minutes to tear through Rochester, but the institution it helped birth is going strong in our communities 135 years later and has a lasting place in the annals of medical history. The story, one of human hope and perseverance in the face of natural disaster, is worth repeating in these dark fall days and this Thanksgiving week.

The beginning of the National Weather Service account of the August 21, 1883 tornado is matter-of-fact: “Between 7:00 PM and 7:05 PM, the tornado moved northeast through northern Rochester. Charles Wilson’s barn on College Hill was about the first building struck and demolished.” The level of devastation becomes clear only later in the account and is reinforced by the text of a telegram sent to the Minnesota Governor that evening: “Rochester is in ruins. Twenty-four people killed. Over forty seriously injured. One-third of the city laid waste. We need immediate help.” In the end, at least 135 homes were completely destroyed and another 200 damaged. Thirty-seven people died, and over 200 were injured in what experts later classified as an F5 storm. My own favorite detail from the weather service report is more humorous, capturing the savagery of the winds but ending, all-in-all, happily: “Chickens, absolutely devoid of feathers but otherwise uninjured, were found unharmed on North Broadway.”

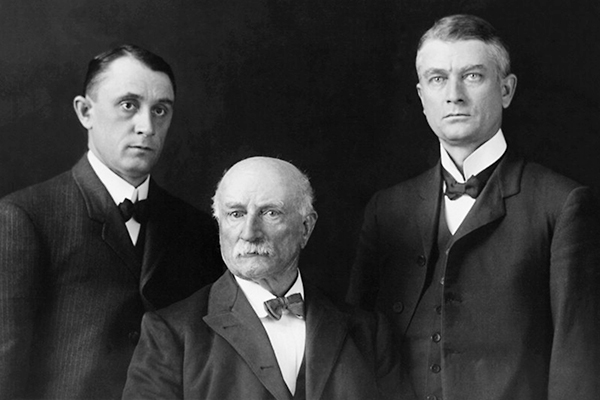

Individual stories from that day, several of them related by Virginia Wright-Peterson in her book Women of the Mayo Clinic, are gripping. Among these stories is that of Dr. William J. Mayo and his brother Charles H. Mayo, who were driving out of town to pick up a sheep’s head for using in surgical experiments. Heading back toward town, they were effectively chased by the tornado, crossing a bridge over the Zumbro River just as it began to collapse and taking refuge next to a blacksmith shop after their carriage was struck by a piece of falling stone. Later, they worked with their father, Dr. W.W. Mayo and other local doctors to treat tornado victims at Rommel Hall, a local dance hall. There was no hospital in Rochester at the time.

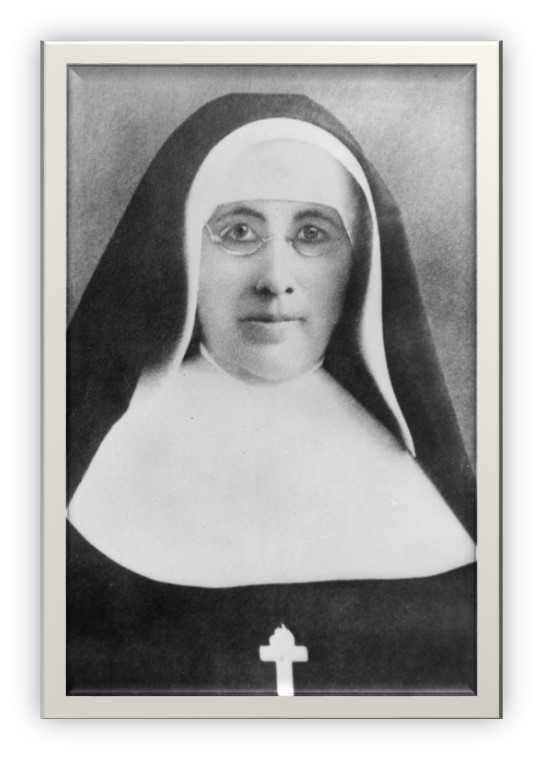

All of that would change after the Sisters of St. Francis got involved in W.W. Mayo’s makeshift tornado clinic. Although they had no training in nursing, they answered Mayo’s call for help. Mother Alfred Moes, seeing the need for permanent medical facilities in Rochester, hatched a plan to found a real hospital. She offered the Mayos a deal: the Sisters would raise the funds for the building and learn nursing, and the Drs. Mayo would be in charge of patient care. Dr. Mayo was reluctant: hospitals at the time were largely viewed as places for dying rather than for healing, and Rochester seemed much too small to support such a venture. Mother Alfred, however, was more optimistic, telling Mayo that “with our faith and hope and energy, it will succeed.” Whether or not he was persuaded, he agreed to the deal, and the two shook hands.

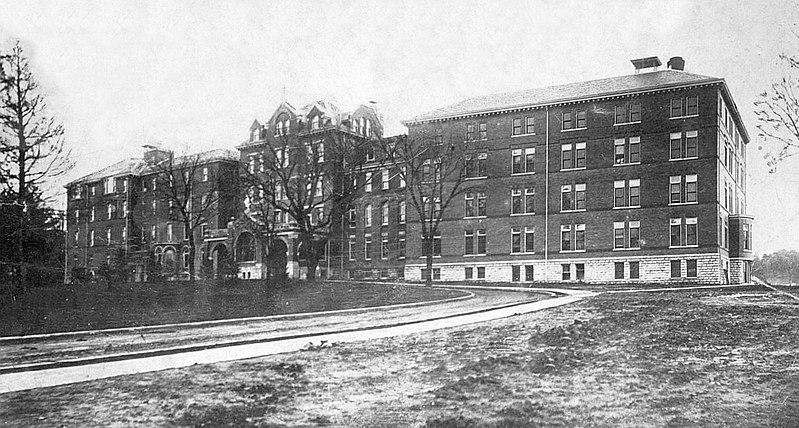

The Sisters began raising funds immediately. In their book, The Tornado: The Storm that Started Mayo Clinic, Thom and Julie Rooke mention activities like selling garden produce, homemade jams, and knitted scarves and sweaters, as well as teaching music lessons. In the end, their efforts were successful, and six years after the storm, St. Mary’s Hospital opened its doors with a single ward containing 27 beds. Will and Charles Mayo, both practicing physicians now, were the hospital’s working doctors, with their 70-year-old father serving as a consulting physician. Both the doctors and Sister-nurses worked long and difficult hours, often beginning work at three or four in the morning and continuing until eleven at night, but the hospital was well-established and began to expand. The Mayo Clinic was on its way.

As we read stories of ever worsening hurricanes, wildfires, and landslides and learn of the damage done to our communities and those of our loved ones by these natural disasters, we are rightly disturbed and saddened. Fortunately, in this Thanksgiving week, we can also be thankful for the ways that disaster can bring people together. And we must look for ways that we, too, can bring good from tragedy.