Northfield Institutions: The Ames Mill

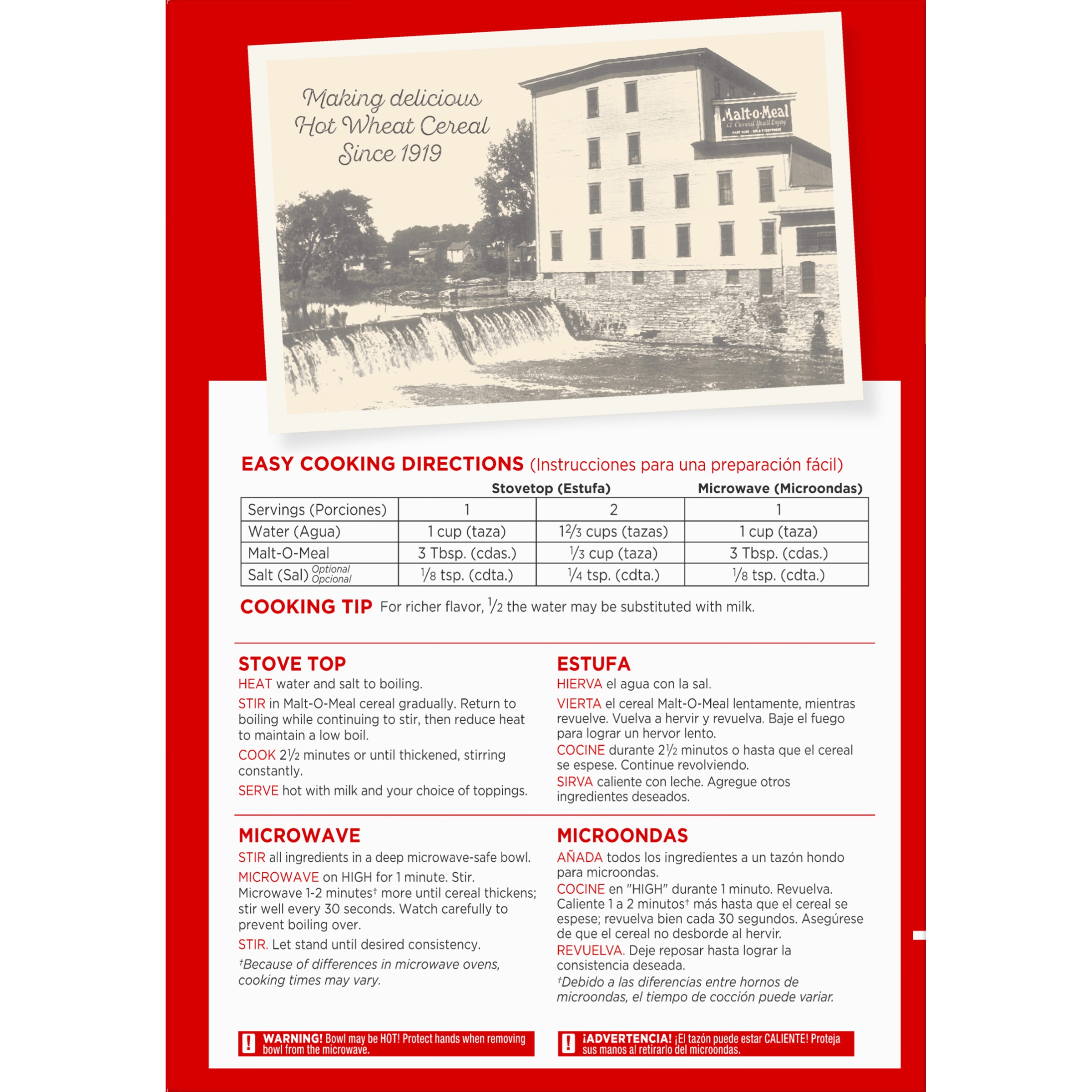

Northfield may be known now for cows, colleges, and contentment, but its history is first and foremost that of a milling town. John North began his development of Northfield with a wooden mill dam in 1855, and he followed with a sawmill and a gristmill just a year later. He sold the gristmill, located on the East side of the river near Bridge Square, to Charles Wheaton in 1859, and Wheaton in turn sold it to Jesse Ames in 1865. Ames had considerably more success than North or Wheaton, and in 1869 he built an enlarged mill on the western bank of the river. This is the Ames Mill that still anchors Northfield’s skyline and produces Malt-o-Meal hot cereal (its picture is on the box!). This year marks the 150th anniversary of the mill’s construction, and it seems fitting to explore the quietly remarkable history of this building that has seen so much of Northfield’s history unfold.

The Ames Mill began as a flour mill – cereal came later – and from the beginning it was a stunning success. Though the new mill’s proximity to the railroad helped, the facility thrived primarily because of the Ames family’s interest in innovation and the very high quality of the mill’s output. The Ames mill was one of the first mills to use a new process, developed among the milling outfits along the Cannon River, that effectively separated the bran and wheat germ from the endosperm (my wife used to work in a flour mill and informs me that I need to keep this detail) to create an extraordinarily pure white flour. In fact, the Ames new process flour was judged “best straight flour” in the country at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

The mill continued to expand and improve over the next few years. In December 1878 the St. Paul Globe stated that the mill had received some 100,000 bushels of wheat that year, and by October 1880, the Star Tribune could report that the mill was turning out 350 barrels of flour a day, up from 125-150 barrels just a few years earlier. The 25 employees of the local barrel manufacturer, Rawson & Co., could barely keep up with the mill’s needs. The Star Tribune article also comments (in the most passive-aggressively partisan way possible) on the comparatively high quality of flour coming out of the mill: “…when shipped to New York it ranks high as compared with other brands sent from Minnesota… The Grange mill is also doing a large and profitable business, and their flour is nearly, if not quite, equal in quality to that made by other flouring mills in this part of the state.”

The mill continued to expand and improve over the next few years. In December 1878 the St. Paul Globe stated that the mill had received some 100,000 bushels of wheat that year, and by October 1880, the Star Tribune could report that the mill was turning out 350 barrels of flour a day, up from 125-150 barrels just a few years earlier. The 25 employees of the local barrel manufacturer, Rawson & Co., could barely keep up with the mill’s needs. The Star Tribune article also comments (in the most passive-aggressively partisan way possible) on the comparatively high quality of flour coming out of the mill: “…when shipped to New York it ranks high as compared with other brands sent from Minnesota… The Grange mill is also doing a large and profitable business, and their flour is nearly, if not quite, equal in quality to that made by other flouring mills in this part of the state.”

Milling in the 19th century was big business, with high stakes and intense competition, and the Ames mill had a part in this aspect of Minnesota history as well. For example, the competition between the Ames mill and the Grange mill, hinted at in the 1880 Star Tribune article, also appears elsewhere in the historical record. According to one document held by the Minnesota Historical Society, the two mills, only a mile apart on the river, were at one point engaged in an all-out feud: “Spring opened with war. The Grange mill backed its water upon the Ames dam, and the Ames mill employed its tail race as a weapon of war to no avail. The result was a battle of lawsuits and newspaper articles, which led to flowery eloquence, but not to profits in flour.” Nor were the Grange mill owners the only ones with complaints. The St. Paul Globe, on January 21, 1879, ran a lengthy and bitter invective against milling companies and their alleged campaign to cheat local farmers. One piece of “evidence” the author produces is the claim by one Pat Butler that both the Ames mill and the Grange mill in Waterford took 36 pounds of wheat from a bushel and returned to him only 24 pounds of flour. Hardly gross chicanery (even now we only get about 42 pounds of flour from 60 pounds of wheat), but it shows a visceral response to milling that is surprising to us today. Even Jesse Ames’s own sons weren’t immune to the controversies arising from their business: in 1888, John and Adelbert Ames sued one another repeatedly over personal debts and the alleged disappearance of some flour from the mill.

Through these early shenanigans and its calmer subsequent history, the mill building itself managed to adapt to changing times and new technologies remarkably well; this adaptability has surely contributed to its long life (it is the lone survivor of the 15 mills once clustered on the Cannon River and has outlasted all of the old mills in Minneapolis as well). The Ames family increased the capacity of the mill in 1873, adding a 30,000 bushel elevator to store wheat on-site, and added a seventh run in 1875. The Ameses also took care to update the mill whenever possible. In 1879, realizing that the flow of the Cannon River was no longer sufficient to drive the mill’s grinding stones, especially in the dry fall, the Ameses installed a steam engine to harness the river’s power more efficiently. When electrical power became available after the turn of the century, the mill converted to electricity, and the steam engine was removed. Although the mill was no longer heavily dependent on the river for power, the owners took care in 1919 to replace the wooden mill dam built by John North with the concrete structure in place today, and the mill’s river infrastructure has continued to be important. After massive floods in 1965 forced the mill to close for almost a week, improvements to the structure seem to have protected the mill well. In the last round of severe flooding in the fall of 2010, the mill reported no more serious damage than 4 inches of water collecting in the basement.

In fact, in spite of the mill’s age and historic appearance, it remains in excellent working condition, still using gravity (as well as a newer pneumatic system) to get materials from one manufacturing process to the next. The mill’s timber frame, which still contains hand hewn timbers from the 1860s, is remarkably adaptable, allowing the introduction of new technologies when they appear. And though the wood construction presents more sanitation and maintenance challenges than newer materials might, the mill routinely receives top marks from building and manufacturing inspectors. Not bad for the oldest industrial building in town.

Of course, the biggest change to come to the Ames Mill occurred in 1927, when John Campbell moved production of his Malt-o-Meal cereal from Owatonna to Northfield and converted the mill from flour milling to cereal production. In the intervening years, Malt-o-Meal has grown, become MOM Brands, and been purchased by Post for 1.15 billion dollars. It has become the 5th largest cereal manufacturer in the country, and its products are sold in 70% of the nation’s grocery stores. The Wikipedia page for Malt-o-Meal lists some 38 cereals, all of which my wife, Kathryn, has announced that we will be trying (she is also demanding that I produce another post on Malt-o-Meal, which seems a more likely prospect). But the original Malt-o-Meal is still produced at the Ames mill, and only at the Ames mill.

Hot Malt-o-Meal cereal only accounts now for a couple percent of Post’s MOM brands sales, but it remains the company’s most widely recognized and beloved product, and its comfortable stability reflects the status of the building where it is produced. Overshadowed economically by Post/MOM’s larger production facility on Highway 19 and much lower profile than its less industrial neighbors along the river, the Ames mill remains a steadfast anchor for Northfield. For all it has seen and done, the mill hasn’t changed much outwardly (the addition in 1879 and subsequent removal of a small 5th story are the most obvious alterations), and it’s easy to pass it every day without really thinking about it being there. Yet its reassuring bulk sits still by the river, quietly successful, adaptable yet unchanging, almost tangibly content with its past, present, and future.